Review of: Solons Götter – Platons Theologie, by Beate Fränzle 2025.

Reviewed by: Thorwald C. Franke 14 January 2026.

Bibliographical data: Beate Fränzle, Solons Götter – Platons Theologie. Mit einem Anhang: Zur Rezeption der sogenannten Kataklysmen-Theorie (Aristoteles, Cuvier, Platon), Volume 30 of the series: Flensburger Studien zu Literatur und Theologie, edited by Markus Pohlmeyer, published by IGEL Literatur & Wissenschaft, Hamburg 2025. 685 pages. EUR 49,-

With her work ‘Solon’s Gods – Plato’s Theology,’ Beate Fränzle has written an incredibly insightful and comprehensive work that touches on many topics and provides the reader with a thousand useful ideas.

NB: All quotations from Beate Fränzle's work in this review were translated into English by the reviewer. You can easily find the German original in the German version of this review.

The relationship between Solon and Plato is the focus and starting point of Beate Fränzle’s reflections. The currently prevailing, typically critical yet insufficiently critical opinion on this subject is represented, for example, by Kathryn A. Morgan: Plato constructed his image of Solon according to his own needs. The Solon we find in Plato is therefore not the real, historical Solon, but a ‘Platonised’ Solon.

Beate Fränzle now turns this thesis on its head: Plato did not have to construct Solon according to his own needs, but rather was inspired in numerous points of his philosophy by the historical Solon. The Solon we find in Plato is therefore, by and large, actually the real, historical Solon. It is not Solon who has been ‘Platonised’, but the other way around: Plato has been ‘Solonised’.

This is also of great significance for the question of Atlantis: for with the credibility of Plato’s depiction of Solon, the credibility of the story of Atlantis, which Solon is said to have brought with him from Egypt to Athens, naturally increases as well.

The thesis is underpinned by an incredible wealth of material and a great love of detail. Numerous correspondences between Solon and Plato are highlighted, in some cases down to the wording and choice of words. Fränzle also supports her theses with many references to current research literature, which often only deals with these topics in passing. It is very convincing.

Solon and Plato are seen to agree on the following topics, among others:

On the fringes of this main theme, Beate Fränzle touches on a wealth of secondary topics, each of which is highly interesting in its own right and opens up whole new worlds for the reader.

Beate Fränzle works very intensively with the research findings on Plato’s unwritten teachings. There are two primordial principles in the categories of knowledge in the analogy of the divided line: the One (hen) and the unlimited Duality (ahoristos dyas). Everything else is derived from these (p. 376 ff.). The divine itself appears in a hierarchical structure of divinity, according to the categories of knowledge in the allegory of the divided line. The higher up in the hierarchy, the more abstract and impersonal: according to Beate Fränzle, the highest idea of the Good is impersonal (p. 262). The demiurge in Plato’s Timaeus creates not only time, but also the traditionally known gods, so that they remain integrated into the new conception of divinity (p. 270).

An ancient topic is the question of where the many parallels between Jewish tradition in the Old Testament and Greek philosophy actually come from (p. 61 ff.). This includes, for example, the development of monotheism, an ethic of justice, or regulations on debt relief. This question was first raised by the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria (c. 15 BC – 40 AD), who believed that the Greeks had ‘stolen’ their wisdom from the Jews. Others believed that the opposite was true: that the Jews had ‘copied’ their wisdom from the Greek philosophers. The debate has repeatedly swung back and forth between these two extremes.

Beate Fränzle puts the cart before the horse, beginning with the thesis of the so-called Axial Age, which was once formulated by the French Orientalist Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron (1731–1805) and later prominently taken up again by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) (p. 61). Finally, she refers to the Assyrian Empire that existed at the time of Solon: this empire influenced both the Greeks and the Jews (p. 81 ff.). The parallels thus go back to a common source. It is important to highlight and document Solon’s travels and intercultural contacts as a long-distance merchant in order to make this influence plausible (pp. 86 f., 123). Ultimately, Solon introduced an oriental political theology to Athens.

Another interesting observation is that Solon was not just any pre-Socratic philosopher, but the oldest of all pre-Socratic philosophers (pp. 62 ff., 121 ff.). Thus, it was not natural philosophy that marked the beginning of the pre-Socratics, as is often claimed, but political philosophy. And political philosophy was not an offshoot of natural philosophy, but rather the reverse: natural philosophy is an offshoot of political philosophy.

The book meticulously traces how the pre-Socratic authors moved towards Solon’s position. This concerns the goodness of the gods, monotheism, the role of poets, the conception of religion, the organisation of religion, and so on. Plato was also strongly influenced by Empedocles (pp. 233–236, 265, 280): Empedocles was the first to use the word ‘trust’ or ‘faith’ (pistis) in relation to the gods. He reflected like Plato on the transmigration of souls, about the gods who are good but not recognisable, and that the goal of ethics is to become like the gods.

Other topics include: the development of Greek literature (pp. 132 ff.), the Greek mystery cults (pp. 103 ff.), which arose under oriental influence during the time of Solon and later merged culturally with Christianity, the role of the Areopagus in the history of Athens as guardians of the laws, which was reformed by Solon and later inspired Plato (p. 66, 147 ff.), the question of theodicy and compensatory justice in the world (p. 159, 225), the relationship between virtue and wealth (p. 182 ff.), the Islands of the Blessed (p. 224 f.), and much more.

When it comes to Atlantis, current academia likes to paint a decidedly bleak picture: Plato was ‘only’ a philosopher who allegedly had no interest whatsoever in historical truth. According to this view, Plato was practically a lying poet who invented the past to suit his own purposes in order to make allegorical statements. – But Beate Fränzle paints a very different picture here: for Beate Fränzle, Plato is even the ‘pioneer of historical science’ (pp. 370, 394). That’s right: it is not Herodotus or Thucydides, but Plato who Beate Fränzle declares to be the pinnacle of the treatment of history in classical Greece.

And Beate Fränzle can draw on a long line of prominent scholars who have contributed to this different, better picture of Plato’s relationship to history, including the following names: Thomas Alexander Szlezák, to whom Beate Fränzle feels particularly close, Konrad Gaiser, Jens Halfwassen, Michael Erler, Hans Joachim Krämer, Willem Jacob Verdenius, Glenn R. Morrow, Markus Enders, Francisco L. Lisi, Hellmut Flashar, Dietmar Hübner, Hans-Joachim Gehrke. Beate Fränzle corresponded personally with some of these scholars and met them at academic events.

Based on the two primordial principles of Plato’s unwritten doctrine, the One (hen) and the unlimited Duality (ahoristos dyas), Plato was the first to develop a theoretically grounded model of history (pp. 376, 380). Beate Fränzle suspects that the complete theory of history could only be found in the unwritten doctrine (p. 412), which is why only traces and fragments of it can be found in the surviving dialogues, especially in the so-called Platonic Myths, but also in the works of later Platonists. For this reason, the work of Origen, for example, is examined in detail (pp. 418-435).

For Beate Fränzle, Plato is of course not a lying poet, but a philosopher who – precisely because he is a philosopher – has an interest in historical truth (p. 369). Glenn R. Morrow’s well-known judgement that Plato was ‘loyal to history’ is also quoted (p. 400). The author examines in detail how Plato received the works of Herodotus (pp. 401 f.) and Thucydides (pp. 402 ff.) and how he was fascinated by Egypt (pp. 546-559).

Plato’s model of history can be recognised if one does not dismiss the so-called Platonic Myths as invented artistic myths or mere fairy tales intended to achieve an allegorical effect, but understands that Plato means what he says there quite seriously – even if this may sometimes seem a little strange to modern eyes.

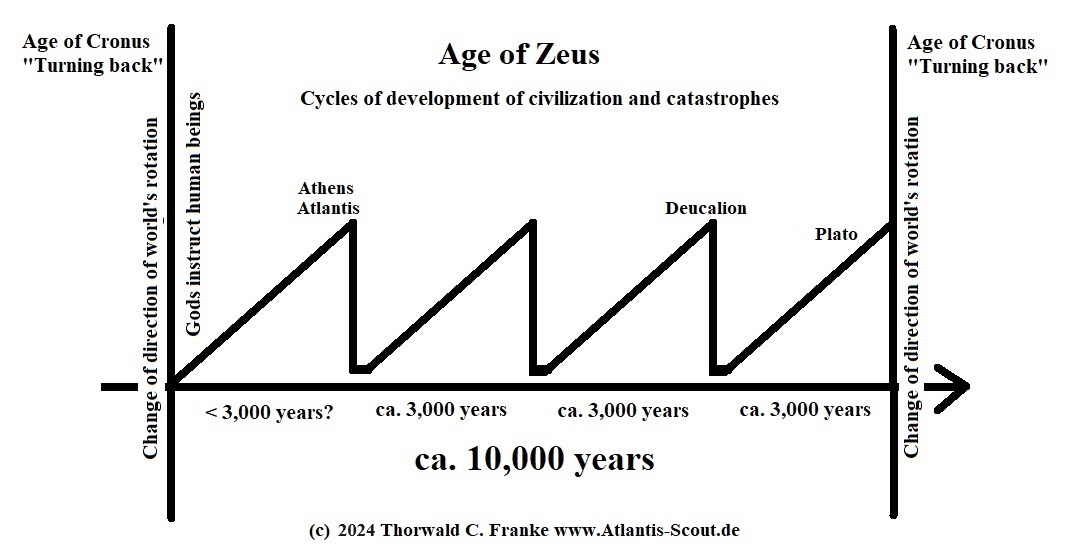

Plato’s model of history essentially consists of a cyclical catastrophism nested within itself several times (pp. 366 ff., 380 ff.):

The comparison of microcosm and macrocosm, the human soul with the cosmos, but also with the state, plays an important role (pp. 376, 385). The three elements of the human soul can be found on all three levels – human, state, cosmos. The so-called ‘nuptial number’ plays a central role in Plato’s model of history: this mathematically calculated number reflects the correct relationship between the various cycles, which a statesman who wants to lead his state well through history should pay attention to. A separate, long chapter in this book is devoted to the examination of the nuptial number (pp. 393, 478-573). It deals, among other things, with various calendar periods such as the octaeteris, the Metonic cycle and the Philolaus cycle, the periods of the Antikythera mechanism and the Athenian wedding month, and, last but not least, a great deal of mathematics and combinatorics.

Beate Fränzle has correctly recognised that Plato believed himself to be living at the end of a 3,000-year period (pp. 374, 391, 388 f.): Culture is highly developed, people are beginning to conduct historical research (p. 371) and understand more and more, until finally the Platonic ideal state will emerge as the culmination and end point of development (pp. 384, 462).

The appendix of the book contains graphical representations of Plato’s model of history, showing both the individual cycles in their progression and the interlocking of the various cycles at different levels.

To illustrate his point, the author of this review has included a graphical picture that he created himself on this topic. Please note: Thorwald C. Franke’s interpretation is not entirely identical to that of Beate Fränzle.

In an excursus, the author addresses the much-discussed question of whether Plato himself believed that his ideal state was achievable (pp. 441-447). The question is answered in the affirmative, but in the sense of an approximation to the ideal state. This approximation is difficult, but possible.

The question of why even the ideal state ultimately degenerates and perishes is also answered (p. 489): firstly, because even philosopher kings are not gods, but fallible human beings bound by the physical fallibility of this world. Secondly, because cyclical catastrophes eventually bring about its downfall.

The question of whether Plato advocated a fundamental renunciation of violence or not is also addressed (pp. 446-456). Beate Fränzle is of the opinion that Plato did not. On this point, Beate Fränzle disagreed with Thomas Alexander Szlezák (p. 238, footnote 587).

The ancient reception history of Plato’s historical model is outlined in broad strokes (pp. 345–440). It appears that the work of Polybius, who primarily described the cycle of constitutions, had a particularly significant influence that extended as far as the Constitution of the United States (p. 438).

A long chapter in the appendix is devoted to the reception of Plato’s historical model by Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), the founder of palaeontology and proponent of a catastrophism theory (pp. 574-630). The appendix also contains an article by the author on the ancient astronomer Aristarchus (pp. 657-670).

Closely interwoven with the two main themes of this book is, of course, the subject of Atlantis, for Solon is said to have brought the story of Atlantis from Egypt to Athens, and the story of Atlantis itself is a testimony to Plato’s cyclical catastrophism. The way in which Beate Fränzle approaches the topic of Atlantis in numerous partial theses raises high expectations: for it always seems to be about Plato meaning what he said, i.e. that it was real history.

Solon is not only Plato’s great philosophical inspiration, but is also presented as a poet in Plato’s sense: For Solon wrote truthfully and was firmly opposed to invention in poetry (p. 291). The statement in Plato’s Atlantis story that Solon would have surpassed both Homer and Hesiod if he had completed his Atlantis epic is also taken completely seriously (p. 296). Solon would therefore really have made use of the literary form of the epic, according to Beate Fränzle, if Plato is to be believed here (p. 195). The most important role that Solon plays in Plato’s work is that of the guarantor of the Atlantis story (pp. 338, 346 ff.).

Unlike Atlantis sceptics, Beate Fränzle does not conclude from the (allegedly) oral tradition of the Atlantis story that it is therefore unreliable; on the contrary, she emphasises the reliability of the tradition (p. 348). Beate Fränzle also correctly observes that the truth of the Atlantis story is not pompously asserted, as many Atlantis sceptics believe, but rather mentioned in passing (p. 349). Nor are the participants in the dialogue portrayed as idiots, as some Atlantis sceptics do, especially with Critias, in order to discredit the story of Atlantis presented by him. Instead, with Szlezák the author maintains the opinion that all participants in the Atlantis dialogues are serious philosophers (p. 349). Nor is there any speculation about a deliberate interruption of the dialogue Critias because everything had already been said; rather, it is assumed that there was a plan to complete the dialogue Critias and also to write the dialogue Hermocrates (p. 349).

It has already been made clear above that Plato was seriously interested in history. But Beate Fränzle also substantiates this with Plato’s statements about soil erosion in Attica since the days of primeval Athens, which are an integral part of the Atlantis story (p. 353 f.). Beate Fränzle emphasises: ‘For Plato, truth (aletheia) is central when he attempts to reconstruct the prehistory of Attica ...’ (p. 395) ‘In order to ensure the authenticity of his Atlantis narrative,’ Plato also traced the chain of transmission precisely (p. 395 f.).

Finally, Beate Fränzle has recognised that Egypt is spared from local catastrophes in Plato’s historical model, which is why the memory of the time before the catastrophe is preserved there (p. 367). It is also substantiated that it is entirely plausible that Solon was actually in Egypt (p. 338 f.).

Beate Fränzle translates the well-known key sentence in Timaeus 26e as follows: It is ‘extremely important that this is not a fictional legend, but a true story.’ (p. 349) She comments: ‘This pointed formulation by Socrates seems to me to be just as serious as his characterisation of Timaeus as a prefiguration of the philosopher-ruler in the ideal state.’ (p. 349) Beate Fränzle therefore sees no irony here that would reverse the meaning of the sentence.

Finally, Beate Fränzle, with Tanja Ruben, refers to the intertextuality of the Republic and Timaeus-Critias (p. 295): What Plato means completely seriously in the Republic, including that the ideal state allegedly already existed in the past, has a correspondence in the story of Atlantis.

In short: Solon and Plato are true philosophers and true poets who mean everything seriously, truly and realistically, and everything is meant seriously, truly and realistically, as Beate Fränzle – it seems – says and shows again and again. We also recall her article ‘Solon bei Platon’ from 2023, which said exactly that without any discernible reservation.

Unfortunately, however, on p. 352 Beate Fränzle makes a very surprising shift away from the reality of Atlantis: ‘The truth content of the lógos ap' Aigýptou that I postulate therefore refers, on the one hand, only to primeval Athens, not to the legendary Atlantis, and, on the other hand, only to the 'laws' (...) of primeval Athens, not to their érgoon kálliston (...), that is, their victory over the Atlanteans.’ Along with Szlezák, she accuses Atlantis proponents of ‘literary ignorance’ and ‘naivety.’ Atlantis is only true in a ‘historical-philosophical-model’ sense (p. 354).

But the truthfulness of primeval Athens is further restricted: at most, the state order of primeval Athens can be granted historicity, but only in the sense and within the framework of Plato’s historical model, ‘which extrapolates into the distant past’ (p. 354). In other words, Plato assumes that a real primeval Athens existed historically, but this information does not come from tradition; rather, it is a conclusion drawn by Plato from his historical model. Beate Fränzle therefore consistently argues that the entire tradition from Egypt is merely a ‘symbolism of place’ deliberately evoked by Plato (p. 354). So no tradition from Egypt, only Plato’s conclusions.

The references to the reality of Atlantis are thus only literary ‘effects of reality’ in the sense of Roland Barthes. At least, that is the opinion of Tanja Ruben, quoted by Beate Fränzle, who follows in the tradition of French scepticism about Atlantis. Beate Fränzle also cites the opinion of Ernst A. Schmidt, according to whom the truth of the story had to be asserted for literary reasons, but of course the story was not really true, and the audience knew that too (p. 350); this is the same opinion that Hans Herter had already expressed (Herter (1928) p. 44 f.). The story of Atlantis, then, is a kind of novel, which, as an established and familiar literary form, is understood as a novel by the audience without any intervention.

Michael Erler is quoted as saying: ‘Plato is a historian in terms of method, but remains a philosopher in terms of content.’ (p. 396) This brings us back to the crude thesis that a philosopher is not so concerned with the truth. In fact, several examples are immediately given where Plato deviates slightly from known history, such as in his account of the events surrounding the Battle of Marathon (pp. 398-400). The message is that Plato falsifies history to suit himself.

Rarely has the absurdity of the invention thesis been presented as vividly as here. First, there is a lot of talk about Plato having an ethos of truth and poets having to write true poetry, and that Solon and Plato mean everything seriously, truly and realistically – over and over again: seriously, truly and realistically – but when it comes to Atlantis – well then! Suddenly, there is a 180-degree turn and everything has to be fiction again.

It is difficult not to turn this into satire:

Since the two perspectives are so close together here, the contradiction is particularly striking: what a miserable liar Plato must have been, making such a big fuss about the truth and insisting that poets must write truthfully, when he himself lied through his teeth? And then there is Solon, who is presented here as Plato’s great alter ego, who fulfilled all the criteria to be considered a poet in Plato’s ideal state because he wrote truthfully: He is simply shamefully abused by Plato – that scoundrel! – to deceptively authenticate a pitiful lie with which Plato wanted to ‘prove’ his philosophical views. But the ‘proof’ is fabricated and is a lie and a forgery.

In doing so, Plato would not only destroy his personal credibility – if only that were all – but also, of course, the meaningfulness of his entire life’s work. Just imagine: Someone claims to be concerned with truth and presents a magnificent model of history in which Egypt was spared local disasters, which is why information about the time before the last disaster could be obtained from there – and then he simply falsifies (!) this information instead of fetching it from Egypt! He makes it up out of thin air! Primeval Athens is thus supposed to be a pure conclusion without any tradition. And Atlantis is even a complete invention out of thin air!

Any reasonably sensible person would have to say: Good grief, we don't want to hear from this ‘philosopher’ anymore! He can tell us nothing. Let’s chase him off the place! He shouldn't come back to us with whatever he has to say.

If we want to speak seriously again:

Isn't it obvious that Plato, who actually believed that information about the time before the last catastrophe could be found in Egypt, actually searched for such information? Some of this information, which Plato believed to date from this period, can already be found in Herodotus. So why invent a story when, according to the theory that Plato actually believed to be true, there must be real (!) stories like this?

And what good does it do somebody who is committed to truthfulness to invent a deceptive story, instead of highlighting the quality of the story, as he always does? Plato would have had to have suffered a serious break in his biography that led him away from his idealism and made him very cynical in order to do such a thing. But there is no evidence of such a break, nor is there any indication of it. Plato remained true to himself and his principles until the end.

And then there is the eternally false argument about the literary form, which forces us to speak of truth, even though everyone supposedly knows that it is not true, that the story of Atlantis is therefore a kind of novel: but the literary form of the Greek novel, with its typical characteristics, which some people want to see in the story of Atlantis, was not developed until several centuries after Plato. It is simply wrong to say that the story of Atlantis was an established literary form well known to the public, which the public would have recognised as untrue, even though it is presented as (approximately) true and is also completely realistic in the eyes of the people of that time.

The ‘literary ignorance’ of which Szlezák spoke lies rather with himself, we are sorry to say that! Thomas Alexander Szlezák was a great scholar, without a doubt, but here he was, together with many of his colleagues, dramatically off track. The literary and philosophical interpretation of the so-called Platonic Myths is surprisingly underdeveloped in academia, which is at the core of the problem.

And Plato’s falsification of the historical events surrounding Marathon? These are relatively minor deviations from an otherwise real set of facts. The facts are therefore historical in any case. Above all, however, it is not really possible from today’s perspective to understand and decide whether Plato really ‘cheated’ here, or whether he simply believed what he wrote. Some of the cheating consists of omissions. Strictly speaking, however, an omission is not a distortion. There can be many reasons for an omission. It is also questionable whether Herodotus' account, from which Plato deviates, is really correct. We simply do not know. But one thing we know for sure: if the ‘cheating’ in the Atlantis story were as minor as it allegedly is in Plato’s account of the Battle of Marathon, then Atlantis would be a very real place!

Finally, we must denounce the folly of trying to make a sharp distinction between primeval Athens and Atlantis. Of course, this is not possible. Both cities are integral parts of the same story. The information about both cities is said to come from Egypt. But if the information is based only on Plato’s conclusions, why should that not also apply to Atlantis? Just as Athens existed in Plato’s time, so did Persia and Carthage. If Plato concludes that Athens existed in ancient times, why not conclude that Persia and Carthage also existed in ancient times? After all, the alleged mud off Gibraltar also provides a basis for such a conclusion. This sharp distinction between primeval Athens and Atlantis is completely absurd, and it reveals the true motivation behind why Atlantis was declared a myth.

It is crystal clear and obvious what happened here: Beate Fränzle has developed a very straightforward and consistent theory about Plato’s understanding of history, which, when thought through to its logical conclusion, inevitably leads to the conclusion that the story of Atlantis is, of course, entirely serious, true and historical, not only in conclusions but with a real tradition from Egypt. Regardless of the question of how much truth there really is in the story from a modern point of view. This is how Beate Fränzle put it in her 2023 article ‘Solon bei Platon’.

But then, for some reason, Beate Fränzle must have shied away from her own courage. Perhaps she became afraid that her life’s work would not be well received, but rather exposed to ridicule, if she drew this conclusion? That is why she subsequently inserted this distinction between primeval Athens and Atlantis, which is strange in itself, but also does not fit in with what she otherwise writes.

Perhaps Beate Fränzle was also contacted by colleagues who read her 2023 article with horror and insisted that she should not present the Atlantis story as a real historical tradition? This is, of course, pure speculation. But it is strange that the 2023 article expresses no reservations whatsoever about the question of truth, while the 2025 book expresses a very clear reservation.

It is reminiscent of Gunnar Rudberg’s shift, who in his original treatise on Atlantis from 1917 considered it ‘quite uncertain’ that the invention statement in Strabo 2.3.6 could be traced back to Aristotle, but then, in the summary of his late work from 1956, he returned without justification to the opinion that Aristotle considered Atlantis to be an invention: perhaps to ensure a favourable reception of his work?

It gets even crazier. After stating that Atlantis should be understood as an invention (p. 352), there are numerous statements in this book that again point to the reality of Atlantis. The reader can only wonder.

For example, it is discussed that there was no language barrier between the Egyptians and the Greeks, as we know from interpreters (p. 355 f.). In addition, the distortion of tradition in the process of transmission is addressed (p. 355). But what is the point of all this if it is supposed to be an invention based on Plato’s conclusions and not on a tradition from Egypt?

It is also said that the social order of primeval Athens was correctly handed down from Egypt (p. 355). And that Plato was not so wrong with his 9,000 years, because Athens allegedly had a settlement history dating back to the seventh millennium BC (p. 353). We also recall that Beate Fränzle emphasises that it is entirely plausible that Solon was indeed in Egypt (p. 338 f.). What are these statements supposed to mean if they are all just Plato’s conclusions and not traditions from Egypt?

And as always, it gets worse: In a footnote (!), Beate Fränzle refers to a rock-solid existence theory of Atlantis and half adopts it as her own: Against Szlezák’s invention thesis, Beate Fränzle first writes: ‘Of course, it must be countered that Plato’s account of Atlantis could have preserved the memory of a historical natural disaster.’ She then cites, among other things, Glenn R. Morrow’s thesis that Plato’s description of Atlantis may well be based on an Egyptian tradition, namely a tradition about the Minoan culture and its demise! (Footnote 923 on p. 352 f.) Beate Fränzle does not fully subscribe to this thesis; she is only concerned with the catastrophe, but insofar as the news of this catastrophe was handed down via Egypt, she does somehow subscribe to this thesis to some extent – because it is impossible to separate the tradition of the catastrophe from the tradition of the culture that suffered this catastrophe.

Beate Fränzle is on a knife’s edge when it comes to Atlantis: on the one hand, she has developed a theory about Plato’s understanding of history which, when thought through to its logical conclusion, inevitably leads to the conclusion that the story of Atlantis is, of course, serious, true and historical, including the tradition from Egypt. Regardless of the question of how much truth there really is in the story from a modern point of view.

Then Beate Fränzle has made an illogical and strange distinction between primeval Athens and Atlantis, with which she wants to declare Atlantis to be a mere invention.

Yet there are still numerous statements in this book that clearly point towards reality.

The unbiased reader can only conclude that accepting the reality of Atlantis best corresponds to Beate Fränzle’s entire work and would resolve the contradictions and oddities that have arisen in the simplest and clearest way (Occam’s razor). That was probably the original intention – our guess! But for some reason, Beate Fränzle shied away from this, which has led to the current situation.

The critical reader knows how to interpret this and will not allow himself to be deterred by the poorly motivated invention statement from correctly assessing the value and message of this magnificent book.

To conclude the subject of Atlantis, we must clarify a few errors in detail that Beate Fränzle has made, because we do not want these errors to spread. So they must be clarified.

The biggest error is certainly the misinterpretation of the 9,000 years of Atlantis. These are meant literally by Plato and are also understood and interpreted exclusively literally by Beate Fränzle. Hence her speculation that Plato was not so wrong after all, if one follows the settlement history of Athens according to Welwei (p. 353). However, Beate Fränzle is mistaken here. Welwei cannot, of course, find an advanced civilisation in the distant prehistory of Athens in the sense of a primeval Athens. Above all, however, Beate Fränzle has overlooked the historical context!

At that time, the Greeks generally believed that Egypt was 11,000 years old, and older. It is therefore absolutely essential to interpret the 9,000 years of Atlantis against the background of this historical context. So if the legendary Pharaoh Menes supposedly lived 11,000+ years before Solon and Plato, but in reality lived around 3000 BC, then it necessarily follows that the 9,000 years of Atlantis point to a date within the known history of Egypt, after Menes. And this still applies even if Plato had invented everything.

Beate Fränzle believes, rather curtly, that the dialogue participant Critias is the tyrant Critias (pp. 297-299). This, she argues, would cause chronological difficulties. However, she dismisses this lightly on the basis of another error: Plato allegedly invented his dialogue situations very freely and ahistorically. This is, of course, not the case. Although the possibility of an older Critias is discussed, it is summarily dismissed. The reception of the literature on this point is also weak. We note that the dialogue participant Critias is of course not the tyrant, but an older Critias. Just as the young dialogue participant Aristotle in the dialogue Parmenides is not ‘the’ Aristotle, but another Aristotle.

Finally, Beate Fränzle repeatedly concludes from the word akoe that the tradition from Egypt is a purely oral tradition (pp. 295, 347 f., 355, 396). However, the fact that it is primarily a written tradition is overlooked, downplayed or pushed aside (pp. 348, 396). Moreover, the word akoe alone does not necessarily indicate an oral tradition. It cannot simply be translated as ‘hearsay’, even if that is close to its literal meaning. In Plato’s time, the word akoe was used more generally in the sense of ‘lore,’ which could also be written. The word akoe does not necessarily indicate an oral tradition. At least Beate Fränzle did not draw any false conclusions from this: although she only sees the oral tradition, she did recognise that the tradition is presented as reliable (p. 348).

Here we want to collect all possible points of criticism relating to content. But first, high praise: Beate Fränzle has gathered a wealth of material and references in this work. Even where one disagrees, one finds plenty of material to support that disagreement. Beate Fränzle does not usually present her theses in a narrow-minded way, but is open to other points of view.

The author sees two paths for Plato’s theology: one is the path of scientific theology, and the other is the path of a personal approach to religion and God (p. 258). This is to be contradicted. This distinction does not exist in Plato. One could say that Plato wants to make the scientific path his personal path. This does not exclude reasonable subjectivity and the weighing up of uncertain knowledge, on the contrary. But pure, subjective arbitrariness is ruled out. So for Plato, there is only one path.

On the question of the influence of the Assyrians on both the Jews and the Greeks, one would have liked to read more and see more systematic analysis. What exactly are the points and quotations that show the agreement between Jewish and Greek teachings? And which Assyrian sources correspond to this in detail? In addition, it would have been nice to read something about the fact that some similarities are only similarities in later perception and reception. Or that the Greeks, with their tendency towards abstraction, turned the same inspiration into something else. All of this is discussed too little. Ultimately, however, this is a topic for another book.

In some cases, the explanations in this book are too far-reaching. The arc that is drawn is too wide, and topics are dealt with that do not fit the core message of the book. For example, a statement by Eric Voegelin on National Socialism (footnote 5 on p. 35) seems somewhat unmotivated. The same applies to an explanation of what Paul might have meant with his statements about women (p. 112 f.). A statement by Goethe on the subject of the gradation of the divine also seems inappropriate, at least in this context (p. 264).

It is true that the founding fathers of the USA referred to Polybius, who in turn was inspired by Plato (p. 438). However, it is incorrect to say that the source cited also states that the founding fathers of the USA were directly influenced by Plato’s Laws; rather, the source says that Polybius was influenced by it.

It is true that the contrast between the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the strict monotheism of Islam can be traced back to Plato and Platonism (p. 99). However, this is not explained very well. It is also correct that Solon acted as a mediator between conflicting interests in Athens and was therefore able to implement his reforms, just as Mohammed later did in Medina (p. 145). The thesis that the Arab conquest of Egypt led to the preservation of many Greek texts is misleading (p. 91). Initially, the texts were destroyed; the collection of texts began later during the Abbasid period.

The author repeatedly states that it is the current state of research that Plato invented his dialogue situations very freely and ahistorically (pp. 299, 365). This is, of course, not the case.

A major problem is that the author has not developed a deeper understanding of the so-called Platonic Myths (e.g. pp. 88, 224, 271 f., 275) and makes some inaccurate statements about them. For example, she calls the Analogy of the Sun not only an ‘analogon’, which is correct, but also a ‘bildlichen Mythos’, i.e., ‘figurative myth’ (‘eikos mythos’), which is completely wrong (p. 275). Nevertheless, the author has mostly interpreted the Platonic Myths intuitively and correctly by recognising that Plato meant much of it seriously after all.

Beate Fränzle interprets the passage in Gorgias 523a, which most interpreters see as a ‘mixture’ of mythos and logos, as a ‘true narrative’. This is much more accurate than seeing it as a ‘mixture’, because depending on one’s perspective, the story is one or the other, but not a mixture of the two. (The unbiased reader, however, wonders once again how one can correctly see this as a true narrative, while at the same time seeing the Atlantis story as nothing more than fiction: this, of course, does not add up.)

The following comments should be made on the historical view of cyclical catastrophism: First of all, it is questionable whether the total period of one rotation of the cosmos really amounts to 3 x 3,000 = 9,000 years (p. 391). The 9,000 years of Atlantis represent the minimum of such a total period. Considering that Plato also mentions a figure of 10,000 years and that Herodotus even mentions a figure of more than 11,340 years, the total period according to Plato’s conception could well have been 4 x 3,000 = 12,000 years. However, this is unclear.

In the interpretation of the Politicus myth, the ages of Zeus and Cronus are incorrectly assigned. In the reviewer’s opinion, the age of Zeus refers to the ‘forward rotation’ of the cosmos, while the age of Cronus refers to the ‘backward rotation’. Beate Fränzle, however, believes that the two ages can be found within the period of one direction of rotation: first the age of Cronus, then the age of Zeus (p. 386; cf. the graphics in the appendix: pp. 671, 674).

The presentation of the reception of Plato’s view of history by the founder of palaeontology, Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), is commendable (pp. 574-630). However, a clear analysis is lacking, especially with regard to Atlantis (Cuvier did not (!) believe in Atlantis). Likewise, it was not recognised that Cuvier is not alone in his interpretations, but stands in a long line of researchers. Beate Fränzle has identified William Buckland alongside Cuvier, but there are many more researchers! All of this is dealt with much better in the book ‘Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis’ (Critical History of Opinions and Hypotheses on Plato’s Atlantis) by Thorwald C. Franke from 2016. It is a pity that Beate Fränzle did not review this book, as it would have greatly helped her topic.

Here we want to collect all possible points of criticism relating to formal aspects. In general, it should be noted that this book was published posthumously. It can therefore be assumed that the author was unable to polish it as thoroughly as would normally be the case. This is evident in many places. However, nothing is lost as a result; on the contrary, the reader often feels closer to the author’s true and honest opinion, with all its doubts, uncertainties and convictions, than is the case in overly polished publications. In any case, the book is polished enough to be understood well and fluently. There are almost no really disturbing errors, and that in 685 pages!

Somewhat distracting is the fact that there are numbered chapters and unnumbered but underlined chapters, some of which are of equal rank. Also confusing is the abundance of introductions, prefaces, prologues and preliminary remarks, many of which are nested within each other before one finally reaches the main text with the actual thesis. – Some parts would have been better titled as ‘digressions’, which is sometimes the case. It would have been better to avoid the chapter number ‘0’ and instead devote a separate chapter to the Solon passages. Some important statements were hidden in footnotes, which should generally be avoided, but Beate Fränzle is not alone in this problem.

The formatting of the text is problematic in places. In particular, quotations and passages from ancient works could have been formatted more compactly. There is a lot of white space in the sentence here, and the actual passage with the original text or translation could have been better separated from the surrounding explanations in terms of typesetting. The presentation of ancient Greek passages in copied images, instead of setting the text directly in ancient Greek script, is also in need of improvement.

On p. 99, the word ‘religious roots’ should have been used instead of ‘ancient roots’. Explanatory insertions such as ‘(modern Greek Évia)’ after ‘Euboia’ are superfluous. Sometimes there are long sentences in brackets. Some abbreviations are annoying, but you get used to them after a while: M.-E. and E.-E., for example, would have been better written out consistently as Musen-Elegie (Prayer to the Muses) and Eunomia-Elegie (Eunomia poem).

The foreword by Beate Fränzle’s husband, Stefan Fränzle, is somewhat idiosyncratic, but after some consideration, the reviewer has come to the conclusion that this is a good thing! It provides an authentic insight into how someone outside the field views this topic. Those involved in communicating science can learn a lot here.

The satellite photos in the appendix are somewhat unmotivated. Maps would have been better.

Finally, the list of Fränzle’s publications does not mention that she was formerly known as Noack and Noack-Hilgers, and that many of her publications can only be found under this name.

Fränzle (2023): Beate Fränzle, Solon bei Platon, in: Georges Goedert / Martina Scherbel (Hrsg.), Perspektiven der Philosophie – Neues Jahrbuch, Volume 49, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden 2023; pp. 171-208.

Fränzle (2025): Beate Fränzle, Solons Götter – Platons Theologie. Mit einem Anhang: Zur Rezeption der sogenannten Kataklysmen-Theorie (Aristoteles, Cuvier, Platon), Volume 30 of the series: Flensburger Studien zu Literatur und Theologie, edited by Markus Pohlmeyer, published by IGEL Literatur & Wissenschaft, Hamburg 2025.

Franke (2006/2016): Thorwald C. Franke, Mit Herodot auf den Spuren von Atlantis – Könnte Atlantis doch ein realer Ort gewesen sein?, 2nd improved and enhanced edition, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016. First edition was 2006.

Franke (2010/2016): Thorwald C. Franke, Aristotle and Atlantis – What did the philosopher really think about Plato’s island empire?, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016. First German edition was 2010.

Franke (2016/2021): Thorwald C. Franke, Kritische Geschichte der Meinungen und Hypothesen zu Platons Atlantis – von der Antike über das Mittelalter bis zur Moderne, 2nd edition in 2 volumes, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2021. First edition was 2016 in one volume.

Franke (2021): Thorwald C. Franke, Platonische Mythen – Was sie sind und was sie nicht sind – Von A wie Atlantis bis Z wie Zamolxis, published by Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2021.

Herter (1928): Hans Herter, Platons Atlantis, in: Bonner Jahrbücher No. 133 (1928); pp. 28-47.

Morrow (1960): Glenn R. Morrow, Plato’s Cretan City – A Historical Interpretation of the Laws, Princeton University Press, Princeton/NJ 1960.

Beate Fränzle (1961-2024) had a long career as a scholar, as can be seen from the blurbs of her publications:

Beate Fränzle also used to publish under the names Beate Noack and Beate Noack-Hilgers.